Here is an initial overview of the conversation written by Ashleigh Brady reflecting on the panel. (Writers lens: Ashleigh Brady’s pronouns are she/her, and she is a settler-colonial, white, able-bodied, middle-class, cis-gender woman, and an employee in NSW Government as well as a volunteer committee member with the Australasian Women in Emergencies Network).

[Disclaimer: We are only scratching the surface of very complex concepts, acknowledging the depth of existing knowledge, literature and diverse lived experiences that we haven’t captured in this conversation.]

In this rapid deep dive of a 1 hour panel, the re-frame of vulnerability is considering how we can better incorporate lived experiences of diverse communities into disaster planning and processes. Eliminating the idea people are inherently vulnerable or susceptible to disaster impacts, recognising all individuals have resilience and coping capacities that are dynamic and can be better harnessed and supported. In this conversation we acknowledge how community has worked to facilitate and lead solutions, and teach and guide each their communities and other stakeholders before, during and after disasters. This builds on a strengths and human rights-based approach with lived experience perspectives to challenge assumptions that categorise and label individual identities and their needs.

The panellists reflected that when we have authentic Inclusion of diverse voices, we better understand diverse individual experiences. We acknowledge that disaster management needs to centre people and their everyday experiences, to begin to unpack the complex structural factors and systems that are creating social vulnerabilities to disaster risk, which are then exacerbated in a disaster.

The panel all shared the different ways they understand and use the term vulnerable, considering what this means for the people in communities we are working alongside. In some cases it was communicated to reflect disproportionate impacts and risks people face due to a range of factors and experiences including disability. The term was avoided in other community-facing contexts, where panellists shared people did not resonate with the term and do not see themselves as vulnerable, acknowledging these terms can be used to reinforce colonial, paternalistic, deficit framings particularly when used in First Nations Communities.

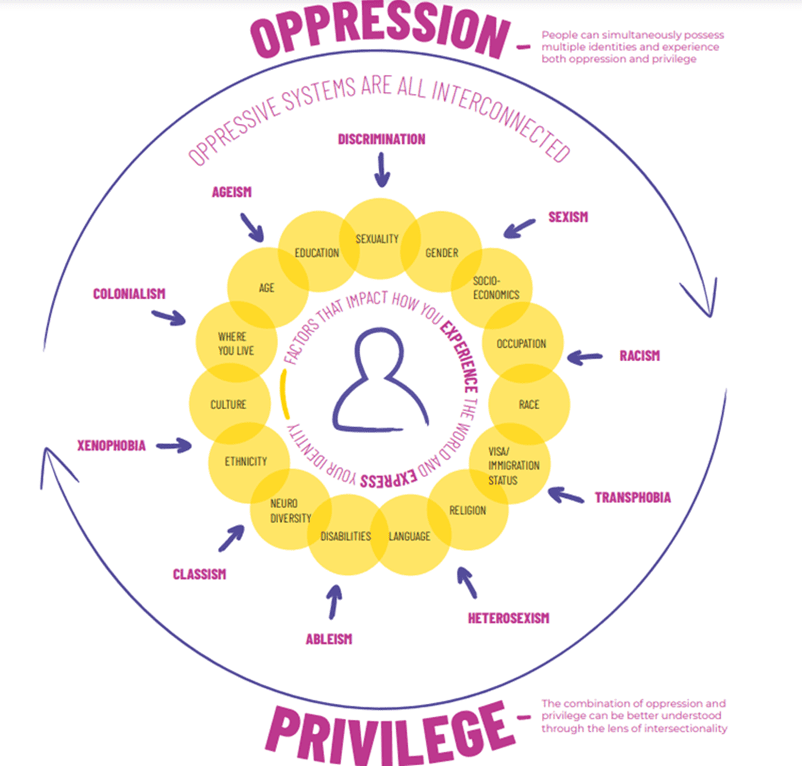

The lens of intersectionality allowed us to speak to the complexity in diversity, and the risks of homogenising and oversimplifying people through terms like ‘vulnerable’. We consider how terms and categories that attempt to put people into boxes can ‘other’ or exclude individuals experiences and reinforce vulnerabilities. We discussed how labels and categories in practice can limit our understanding of the needs complex intersectional and interconnected experiences of people in communities. We reflected on the other fantastic community-centred sessions at the conference, which do reflect the siloed ways we approach inclusion currently, and the need to connect inclusive approaches better to reflect intersectional lived experiences.

We are seeking to avoid the legacies of oversimplified binary approaches to inclusion, where recent progress from gender inclusion has failed to consider intersectional life experiences, and has shown to improve outcomes for mainly for white, middle class, able-bodied, heterosexual, cis-gendered women (see DCA, CARM). This is why we need to move beyond single issue approaches or solutions and meet the community in the reality and complexity of their experience.

Our panel shared stories of community-owned, led and centred recovery and resilience work, through programs including the Disability Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction Program, and the Red Cross First Nations Recovery Programs. Our panellists spoke to the importance of recognising people know what they need, and shared stories of communities coming together to support each other before and in disaster. We also reflected on ways to meaningfully engage with our diverse communities, and the importance of practitioners or people supporting/working alongside community need to be conscious of their bias and be aware of how you identify and seek community leaders.

Stories shared about the Red Cross First Nations Recovery team’s work reinforced the importance of local trusted relationships and connections built from shared lived experiences, in ensuring First Nations community members feel supported and safe to leave their home and go to an evacuation centre, supported by First Nations Volunteers.

We also spoke of the importance of peer leadership, with peer leadership approaches reflecting understanding of diverse range of experiences of disability in particular, and the different types of engagement that is required responding to different experiences, from different elements of visual tools and sensory/stimulus in delivery methods.

The broader benefits for everyone through inclusive planning was recognised through the curb-cut effect example. The curb cut effect exemplifies the accessible benefits for all, after designing to seemingly specific needs, in this case wheelchair access of cross walks. This accessibility feature provides benefits for the broader community including parents with prams, elderly people, cyclists and many more beyond wheelchair users.

This conversation calls on us to continue to improve our understanding of individual experiences and unique needs in local communities. We need to prioritise and centre these complex individual realities and experiences in everything we do, to resource and enable community to be the leaders and agents of change in disaster planning, strengthening equitable resilience to increasing climate and disaster risks leaving no-one behind.

*Term Explainers:

In this conversation the concepts are framed as below:

Vulnerability can be a challenging concept to understand because it tends to mean different things to different people and because it is often described using a variety of terms including ‘predisposition’, ‘fragility’, ‘weakness’, ‘deficiency’ or ‘lack of capacity’. We recognise there are many factors that drive vulnerability, in this context we are speaking of social vulnerability in disasters, which affects disproportionate risks and impacts to people in disasters. We need to recognise that disadvantage and marginalisation can place people at greater risk due to their race, gender, ability and other factors of difference, but we need to call out the deeper systems enforcing this disadvantage like racism and discrimination and structural violence.

An Intersectional lens recognises intersecting experiences of disadvantage (and privileges) that individuals experience or identify with(such as gender, race, class, sexuality, ability, etc.) intersect and interact, shaping their unique experiences and position to be more or less vulnerable to disaster risk.

It emphasises the understanding that individuals cannot be fully understood by considering only one aspect of their identity, but rather, their experiences are shaped by the interconnectedness of various forms of privilege and marginalisation. By understanding the complexities of these intersecting identities, we can better address the root causes and drivers of risk, like systemic inequities that contribute to vulnerabilities in the face of disasters.

Intersectionality allows us to move beyond binary and homogenised understandings of people that tend to be labelled as ‘vulnerable’, such as women, people with disability, LGBTQIA+, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and more. By adopting a gender-transformative approach, we aim to challenge traditional binary (male/female) gender roles, promote gender equity, and empower women, gender-non-binary and gender-diverse individuals as leaders and agents of change in disaster-affected communities.